|

No-one asked why we held a Burns Supper in respect of Scottishness – that seemed like an obviously good idea – but not a few have wondered how the Guild could host an evening which seemed to celebrate an infamous Freemason of questionable morals.

To answer that question it’s important to set out an important principle: we ‘do different’ here at the Guild. Just because other groups that like beautiful Liturgy think in a certain way, that doesn’t mean we have to. We are accountable to the Lord, and to our Bishop, not to the court of public opinion. We will have no Shibboleths here.

That said, how are we supposed to deal with historical figures – poets, artists and suchlike – whose ideals are not wholly compatible with the Catholic Faith? It’s important to remember that prudential judgment applies in such circumstances – we are obliged to weigh up competing goods against problematic themes and come to a conclusion in good conscience. That is also to say, Catholics of good will may conceivably come to different conclusions, and still be within the bounds of an acceptable moral choice. This is not the case in matters of the fundamental moral law.

Burns Night is not about Freemasonry, it’s about Scottishness – and whilst Burns was certainly a libertarian, and a Mason, his Freemasonry was a protest against the constricting Protestantism of established religion in Scotland, which sought to extinguish all remembrance of the Mass. Put bluntly, the Calvinism of the Scottish Kirk was much more an enemy to the Catholic Church than the Lodge of Burns’s day.

The Freemasonry of the Eighteenth Century was not the same as the syncrestic anti-clerical movement that it later became. In Scotland it was deeply allied to Jacobitism, which was support for the deposed (and deeply Catholic) King James II of England, VII of Scotland.

It is said that the Pope’s first condemnation of Freemasonry, the Bull In eminenti of 1738 was the consequence of failed political play by James’s son and heir, James Stuart, the Old Pretender, resident in Rome at the pleasure of the Pope, father of Bonnie Prince Charlie, and illustrious member of the Roman Lodge.

The Old Pretender wanted Pope Clement XII to condemn only those Lodges that supported his rivals, the Hanoverian Protestant Monarchs, who were occupying the throne he considered his by right. However, politics came into play, and the Pope decided to outlaw membership of all Lodges for Catholics on account of their secrecy and non-sectarian principles.

As a vehicle for toleration and liberalism, Lodges failed miserably: far from evolving into a kind of Court of the Gentiles, they turned on the Catholic Church and pursued a path of militant secularism deeply antithetical to the Church – and deeply wrong. But we are entitled to judge historical figures by the standards of their day, not with the hindsight of subsequent events.

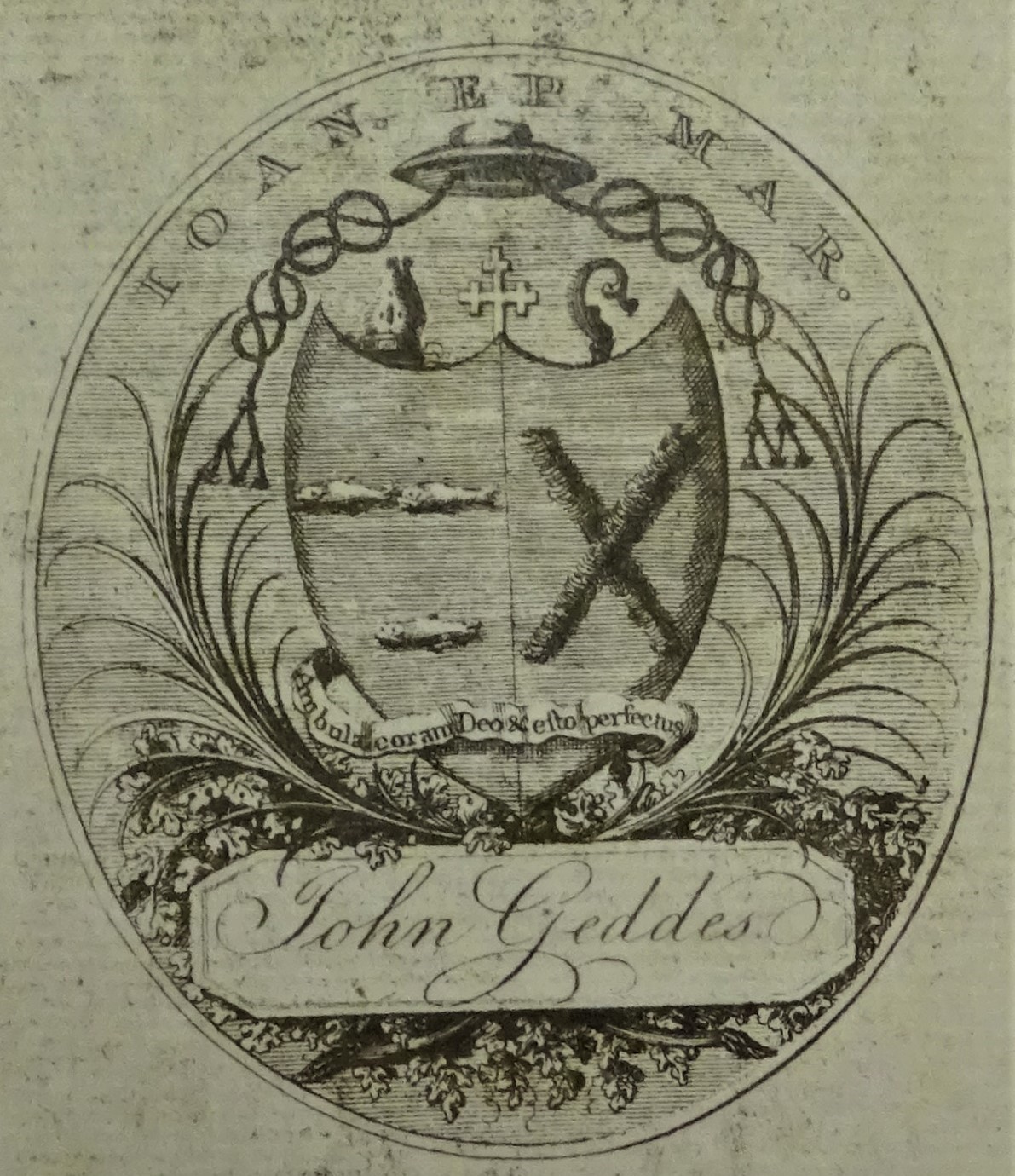

Burns himself was friendly to Catholics: he struck a notable friendship with Bishop John Geddes (1735 – 1799) the Vicar Apostolic, appointed by the Pope to look after persecuted Scottish Catholics in penal times. Bishop Geddes, by return, was fond of the poet – and had copies of his poetry purchased for the Scots seminaries in Paris, Salamanca and Rome. Bishop Geddes therefore made a prudential judgment on whether Burns’s works could be enjoyed by those studying for the priesthood – fully apprised of the proscriptions of In eminenti – and decided that its terms did not prevent him from doing so. It is therefore to Bishop Geddes that I defer for support when considering whether or not the Guild can enjoy Burns Night. We will raise a toast to him next year.

PRAY