|

We have entered into Septuagesima, the season before Lent begins, when our fasting and our corporal chastisement are done out of devotion, not obligation. This is spiritual training of the highest order, that we should practice any Catholic devotion, not because we are obliged to, but out of love. Septuagesima, these three short weeks before Lent, is a time to get our house in order. After all, if you knew that the flood was coming, you would have built an Ark, just as Noah did. These weeks are the time to build the Ark. So, what are you going to do to prepare yourself for the great and holy season of Lent?

It is important during Lent that we fast and feast appropriately. I should remind you that Sundays are not counted among the 40 days of Lent. When you do the counting – Sundays are excluded (6 x 6 = 36 + the 4 days from Ash Wednesday). You may have particular reasons to continue your fasting – and that is as well. Perhaps you are giving up something; perhaps you’re taking on something. That is certainly up to you. But please don’t make Lent stricter than it is. We don’t have the right to make the Church stricter than she really is with us.

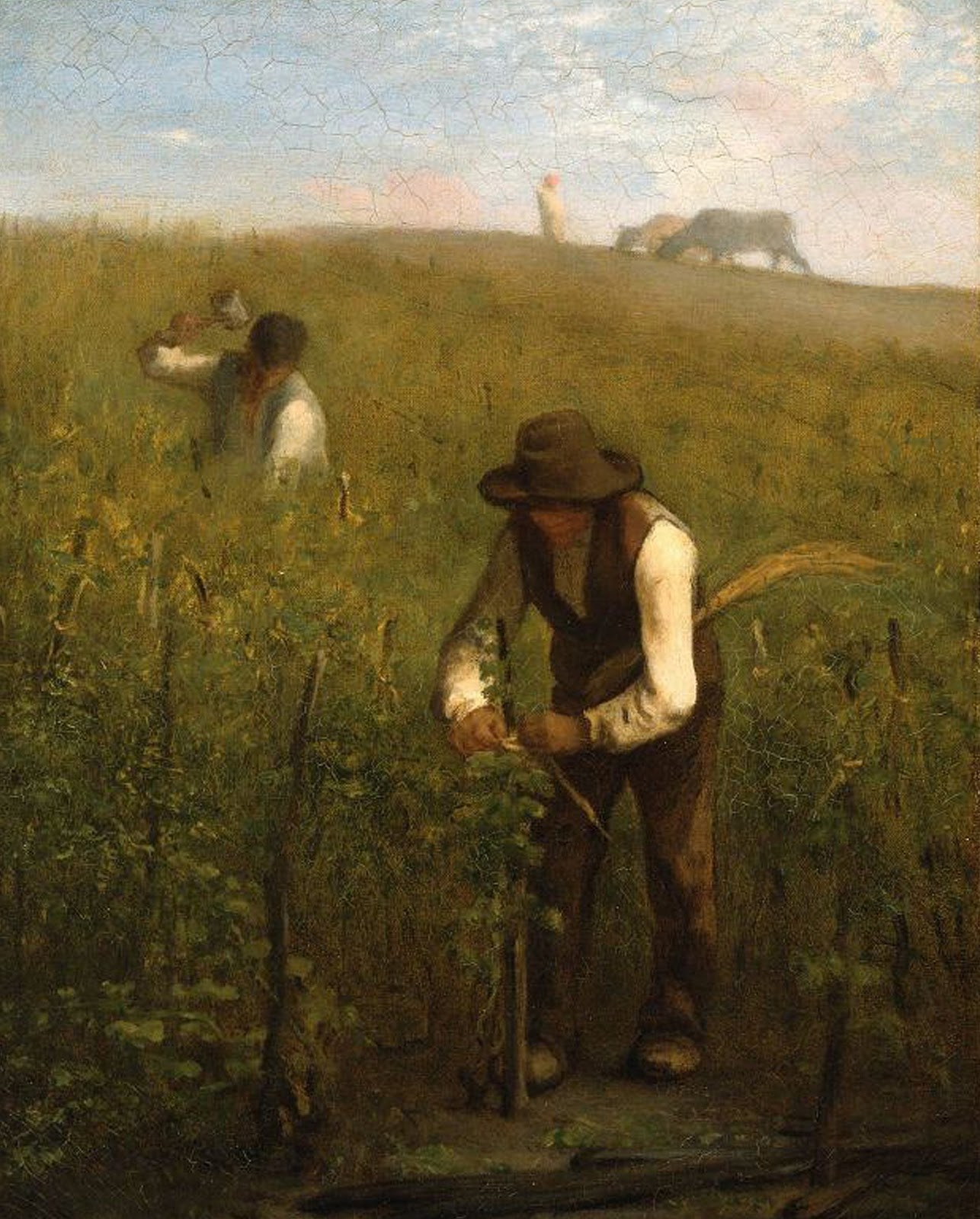

Jesus says in this Gospel for Septuagesima, “The last shall be first, and the first shall be last.” How frequently in our lives have we heard those words of the Lord? But what do they mean? First, we need to look at the context of this parable. The parable of the Vineyard Laborers is a response to the question raised by the Apostle Peter, and I paraphrase: “We left everything. What will we get in the kingdom of heaven?”

Peter’s question is itself a response to another parable the Lord gives, that of the Rich Young Man, which ends with these same enigmatic words: “The last shall be first, and the first shall be last.” The two parables, then, are closely linked and should be read as a kind of diptych. They are two sides of the same coin. The response to the parable of the Rich Young Man was something of dismay. “Who then can be saved?” they ask of the Lord. “For men, it is impossible, but nothing is impossible for God” is the Lord’s reply. This adds the context to the saying that it is difficult for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven: for man it is indeed impossible, but for God, nothing is impossible.

Peter, however, has not quite understood or taken onboard that qualification the Lord gives. “What will we get in the kingdom of heaven? We left everything for you. What will we get?” Make no mistake, the parable of the Vineyard Laborers is a moral correction of the Apostle Peter, and it is a correction which is essential to understanding the Christian life: “The last shall be first, and the first shall be last.”

As with many of the Lord’s sayings, these words seem at first to be a conundrum. To focus on what He means, we need to do a little bit of Greek homework, as we often do. Remember when we read protos, ‘first’ and eschatos, ‘last’, they always have a double meaning, but that meaning is weaker in English than it is in Greek. The primary meaning in Greek, like in English, is to do with chronological time: one runs a race and comes in first, whereas another one comes in last. But there is also second meaning that is equally strong, signifying honor, or pre-eminence. For somebody to be described as protos, could mean he is of a high stature, dignity. It is clear the Lord is using both meanings when He says “the last shall be first, and the first shall be last” is not a Shakespearean riddle, like the witches in Macbeth who say “fair is foul and foul is fair”. Not that: it is in fact a mixed metaphor. The Lord uses both of these meanings of ‘first’ and ‘last’ alternately. The last in time may be the first in honor; the first in time may be the last in honor.

In short, God’s favor does not correlate to the time that we have served Him. It is not linked to the hours we have spent responding to His call. Instead, His favor correlates to our capacity to receive grace. It is perfectly possible for somebody to be called by God rather late in the day, but to have a greater capacity for grace than somebody who was called from their earliest days, and yet somehow has not received that same capacity for grace. We cannot say to the Lord, ‘Because I have been a good Catholic x years I deserve a greater share in heaven than somebody who’s been a Catholic for two years’ or ‘I labored for you. I suffered for you in the name of the Church for 50 years. This person did not suffer as much, or at all, and yet you seem to be giving him more than me.’

Beware of spiritual pride. Beware of making a judgment against your brothers and sisters in this way. What does spiritual pride sound like? How about:

“I’ve been Catholic all my life,” or,

“I went to Catholic school, Father,” or,

“I’ve been attending the traditional Latin Mass for 30 years before all of you, way before Summorum Pontificum. I attended the traditional Latin Mass in the basement at 3:00 PM on a third Sunday once a month for decades before it was fashionable.”

Those are all examples of explicit spiritual pride, because, like the workers in the vineyard, such a person is expecting some greater favor from the Lord from the time spent laboring. The Lord does not work this way. Quite frankly, newcomers may be holier than you or me, because they may have greater capacity to respond to God’s grace – or respond to that grace more fully than you or I ever do. There is no injustice in that. God, who is all good, does not distribute goods evenly. It does not please Him to do so.

The second meaning of the parable of the vineyard workers is that labor is its own reward. Earning a denarius is not the reason that we go into the vineyard. Working, in and of itself, is the reason we go into the vineyard. The service of the Lord is perfect freedom. Actually doing the Lord’s work should cause us joy, even when we have to do so in the heat of the day, when it is scorching temperature, because that very labor is a participation in the Lord’s work. A greater participation in the Lord’s work means that we have the greater opportunity for holiness. To be in the vineyard is the precondition of the reception of grace. The denarius that is given is not equivalent to sanctity; that is: holiness or sainthood. The denarius is actually salvation. Everybody is offered the same opportunity of eternal life, of being saved, of being with the Lord forever, whether each came early or late to the vineyard. Please do note very carefully that the claim is not made in this parable that heaven is perfect equality: in other words, it is not that you pay your denarius and get into the country club. Again, responding to the idea of capacity for grace, we can see that in heaven, we are precisely not all equal.

St. Jerome wrote it is not time but faith that is appealing to the Lord. The gift of salvation is unmerited, totally unmerited, and is offered to all. But our holiness is in proportion to our capacity for grace. That relationship between grace and merit is engaged in this parable most strongly. Where does it leave us? Well, it leaves us with a chastening, a spiritual chastisement to avoid the temptation to look at others compare their relationship with the Lord with our own. The same offer of salvation is made, and you or I, in receiving our particular judgment before the Lord, will be satisfied with the judgment of a just judge. It will not be possible to be dissatisfied and think, “Oh, the Lord has somehow got it wrong.” The Lord cannot get it wrong.

Therefore, during our lifetime, we must strive for holiness; strive to be receptive. If God has you work in the heat and scorching temperatures, then be grateful! Be glad for that, because you have been given a participation in that backbreaking work of saving the world. Rejoice in it! By that, you may win your soul. But do not compare yourselves with others: God has made a pathway for them. It may be that in response to their blindness, suddenly the Lord brings them into the fold in a spectacular way, and their previous life was merely a counterpoint to show other people how wrong those choices are. We cannot judge those matters: they are for the Lord to reveal.

Sufficient grace has been given to each one of us: bespoke and tailor-made; sufficient to deal with all the problems, all the sufferings, all the trials and tribulations of life, allowed by His permissive will. He has laid the table, and the great gift of grace has been given to respond to these tribulations, sufficient grace to be a great saint. It is through those trials and tribulations that sanctity is achieved. May this Septuagesima stretch our hearts and wills to receive our fullest capacity for grace!

PRAY